A Conversation About Bike Fit With Dr. Andy Pruitt

I have a confession to make. After 10 years of serious cycling, I finally got my first real bike fit a few weeks ago. Yes, despite investing thousands of dollars over the years in equipment, nutrition, and training, I neglected the most obvious improvement I could’ve made in my riding, and my performance suffered as a result.

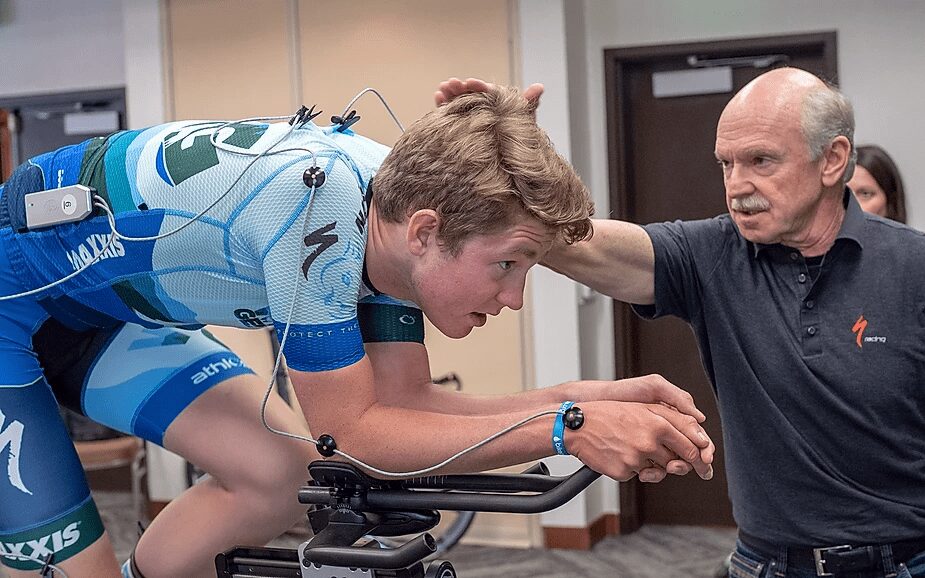

This experience got me thinking about the oft-misunderstood concept of bike fit, so I reached out to Dr. Andy Pruitt. Andy is synonymous with bike fitting, with over 40 years of experience working with some of the world’s most famous cyclists. His long list of credentials includes co-founding the CU Sports Medicine and Performance Center and consulting with Specialized for 20 years. If you’ve ever used a Body Geometry shoe or Power Saddle, you’ve touched a product Dr. Pruitt helped design, and his research and innovations continue to shape the field of bike fitting more than anyone else’s. We spoke for about an hour on all things fit-related.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

TrainerRoad: Let’s start with a basic question. Why is bike fit important?

Dr. Pruitt: It’s fairly simple, in that the bicycle is a fixed machine. It’s adjustable, but it’s fixed when you’re riding it, and a human is an incredibly adaptable living organism. We are incredible adapters- think about riders during the Tour De France. Sometimes, a rider gets a spare bike or is forced to finish the stage on a teammate’s bike and the saddle height is 2cm off. That rider will adapt and get to the finish.

So we can adapt so well to the misgivings of that fixed machine, but it’s in that adaptation process where we get overuse injuries. Asking your patellar tendon to adapt to a saddle that’s 2cm low might seem to feel ok, but might eventually leave you with patellar tendonitis halfway across Iowa. Your body can’t keep up with that adaptation and you end up with injury. So my whole goal and reason for bike fitting is to make the bike look like the individual riding it. This includes their feet, their knees, their hips, and their back. We want to make the bike look like the person to minimize the body’s need for adaptation.

Interesting. So how do amateur athletes identify a good bike fitter, to help us achieve that goal?

When I first started in the late seventies, there weren’t any experts, just maybe 5 of us around the world that communicated and trusted each other. 40 years later, everyone thinks they’re a bike fitter. It’s gotten a bit diluted at this point, and I think you need to be really careful when you pick a fitter as a result.

I think it needs to be someone with technical training who can perform a good cycling-specific physical assessment. A good fitter needs to identify your foot mechanics, your knee alignment, your flexibility; when understood correctly these can make one bike fitter better than the next one. Even if they’re using a fit system, someone has to interpret all the data, the system alone can’t do the fit. But when the fitter is able to make good decisions based on physical assessments and the data, then you’re on to something.

So it’s got to be someone who can really learn the athlete. If your buddy had a good experience with them and went in with knee pain and came out with none, I’d start there. Reputation and success with other athletes are important, and if they have a network of medical folks who refer to them too, you’re probably on the right track. That’s not a short answer but it’s really a very complicated question.

Once we find a fitter we trust, how often should we be re-fitted or make adjustments?

I would encourage an annual fit review, and if you’ve got a good fitter it should be on their menu. Kids should be reassessed every time they have a significant growth spurt; I once worked with a mother who went through 3 bikes in one season for her growing 15 year-old. But for the average rider doing 2,000 miles or more a year, it should be once a year just for a check in, and probably more often for older athletes. If ever you develop saddle pain, hand numbness, or back pain, it’s not a reason to stop cycling, but it’s definitely a reason for a reassessment. These are things you should not put up with.

You famously lost part of one leg in an accident when you were young, and later went on to win two paralympic world championships, so I know you’ve personally dealt with physical asymmetry on the bike. How common is it for athletes to be asymmetrical, and how should we address this?

In 45 years of sports medicine practice, I’ve never seen anyone who is perfectly symmetrical, but everyone is different in their ability to absorb it. A 3mm leg length difference might be catastrophic for one rider, while another person learns to compensate and accommodate it. But everybody has asymmetries- everybody! I think if they bother you, and you’re aware of them and they create some kind of back pain, or imbalance, or saddle sore, then they need to be addressed.

In 45 years of sports medicine practice, I’ve never seen anyone who is perfectly symmetrical.

I was working with an athlete at the world championships one year, and I noticed she was riding way off to one side. That night at the hotel I examined her and found a leg length imbalance, and I made her a 3mm shim for her cleat out of a pop can. She felt great with the shim and won the world TT championships, but 6 months later I rode with her and she was now leaning in the other direction and complaining about her back and groin. We removed the shim and she was fine. Whatever it was- volume, intensity, whatever- had gotten to her during the lead up to the race and her imbalance needed to be addressed. We addressed it, it healed, and she eventually no longer needed that shim. So any time you make an adjustment for asymmetry, it’s going to feel good at first, but remember that the body is adaptable.

Let’s talk about fitting mistakes. What common things do you see riders doing wrong?

Mountain bikes now are coming with very short stems and incredibly wide bars. I understand there’s a downhill rider who needs that long lever to control the front wheel in a rock garden. But you’d never do a push up in that position, and If you sell the average rider a bike with 800mm bars and ask them to ride for hours, they’re going to come home with neck and shoulder pain.

On the road, everyone wants to look like their heroes on TV. I remember in the days of Greg Lemond that meant the saddle was slammed all the way back. Greg has long femurs and perfect biomechanics and was incredibly flexible, but other riders ruined their hamstrings trying to imitate this position. The knee wants to be over the pedal spindle, it’s the position of greatest leverage. By pushing yourself way back, all of a sudden your hamstrings are trying to work really hard, and you develop tendonitis.

If you look at the pro tour now, they’re doing the opposite. Most of the time they’re ending up with their knees about 2cm in front of what we used to refer to as a “neutral” position. But there’s a self-selection that occurs when we ride; or bodies know how to produce power. When the gun goes off you’re going to naturally scoot forward on the saddle. My philosophy has always been to set the rider up in a neutral position under moderate load, so the rider can then move around on the bike to find what they need for the moment or terrain. If you set your bike up only to go hard, you won’t be comfortable going easy.

Adaptive Training

Get the right workout, every time with training that adapts to you.

Check Out TrainerRoadClearly, fitting is extremely complicated. What adjustments can an athlete safely do on their own, without any expertise?

90% of all humans need some form of arch support. If you’re having knee or foot pain, you could easily experiment with different over-the-counter arch support, without spending a lot of money. This can solve numb foot or medial knee pain resulting from arch collapse.

One piece of advice from the old 1970s Italian fit bible that still rings true relates to saddle height. If I’m sitting comfortably and stably on my bike on an indoor trainer, I want to be able to put my heel on the pedal at the bottom of the pedal stroke with a fully extended knee. Sure, heel thickness and pedal height varies, but if you can scrape that pedal with your heel without a reach of the pelvis, that’s a good starting saddle height. It might not be the most powerful position, but it’s a safe place to start.

People want a formula… everyone wants a tool that can do fitting for them, but it’s just not that simple. Bike fit is a combination of experience, art, and science.

As far as fore-aft adjustments, it’s harder. I would chase comfort, but moving your saddle forward is not a solution for a stem that’s too long. You’ll end up with your knee too far forward, putting stress on the patella and quad tendons. So while saddle height and arch support are easy to do on your own, reach is a tough one. In any case, if you can’t eradicate pain or make yourself comfortable, stop. If you’re trying to solve pain and you can’t solve it, stop.

I don’t want to just plug an old book, but my book Andy Pruitt’s Complete Medical Guide For Cyclists does address many of these issues, such as identifying all different knee pains. It’s an old book but if I lived somewhere without access to a good fitter, I’d get myself a good book.

You were instrumental in developing Specialized’s popular Power and Mimic saddles. What input can you offer on saddles, and the trend towards shorter saddles in particular?

I’m not sure why saddles were traditionally so long, aside from the fact that just one or two manufacturers made all of them. But how many of us really use the nose of a long saddle? The length of the saddle nose is really not important, a saddle is all about skeletal support and we don’t want to sit on tissue that’s not meant to be weight-bearing. The power saddle started as a saddle for Evelyn Stevens in her pursuit of the world hour record. We always intended it as a unisex saddle, and it became the most popular saddle in the world, bar none.

Saddle choice is a very personal choice. I highly recommend you go somewhere that will measure your pelvis. If saddle discomfort, urinary discomfort, sexual disfunction, or numbness is an issue, you need to know where you’re sitting and for this I really like the use of a pressure map to help you find the right saddle and saddle position. Position is important- the right saddle in the wrong place is as bad as the wrong saddle.

The saddle is ground zero in bike fitting. It is where you start. If you change your saddle, your whole fit has changed, your whole pelvic relationship to the bike has changed. So if you’re in the middle of a long bike fit and you change your saddle- start over. Maybe that’s a good hint for your readers (in choosing a fitter): if your fitter changes your saddle and doesn’t re-check the saddle height and fore/aft and reach, get your money back. When you change your saddle, the whole thing changes.

That seems like a good note to end on.

I could obviously speak on this all day, but really, people want a formula. Everyone wants a tool that can do fitting for them, but it is just not that simple. Bike fit is a combination of experience, art, and science.

Photos courtesy Dr. Andy Pruitt / www.andrewpruittedd.com