What Is Lactate Threshold and How To Train It

Lactate, Lactic Acid, and Lactate Threshold. You’ve heard these terms before, and probably used them yourself. For decades, athletes have believed that lactic acid was responsible for the burn in their legs during exercise, and considered lactate to be a harmful byproduct of muscular metabolism. We now know that neither of these are true. What does the science actually say?

Key Takeaways:

- Lactate is produced by muscular metabolism and is more than just a waste product

- Lactic acid is not the cause of burning muscles

- A dramatic rise in blood lactate levels known as Lactate Threshold occurs during high-intensity exercise

- Lactate Threshold is highly trainable

- Improving your Lactate Threshold can significantly increase your ability to ride at intensity

What Is Lactate

Lactate, or more specifically l-lactate, is a substance produced by the muscles during exercise. With the chemical formula C3H5O3, lactate is the conjugate base of lactic acid, but the two are not technically the same. Despite frequent mentions in sports literature and in conversation, most scientists currently believe the body does not produce significant amounts of lactic acid at all, and the use of that term in connection with exercise is generally incorrect. Unlike lactic acid, production of lactate is a very real phenomenon and is a crucial part of how the muscles metabolize energy.

Lactic acid was first discovered as a byproduct of bacteria found in sour milk. This is why it shares the lact– prefix with words such as lactose and lactation. However, apart from these linguistic roots, Lactate and Lactic Acid have no unique connection to milk. Instead, lactate is a common biological compound, produced in humans by the metabolism of glycogen and glucose in the muscles.

Adaptive Training

Get the right workout, every time with training that adapts to you.

Check Out TrainerRoadAs glycolysis converts blood glucose into ATP and pyruvate; some pyruvate is then converted back to ATP by the mitochondria, and some is converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase. While this lactate was once believed to be just a waste product, recent research instead suggests the body actually uses it as a secondary fuel in the muscles, heart, brain, liver, and kidneys.

What is Lactate Threshold / Maximal Lactate Steady State

Lactate is continually produced in the body and a small amount is always in circulation in the blood, normally around 1-2 mmol/L. Lactate production and uptake increase in tandem during exercise and balance each other out at low intensities. As exercise becomes more vigorous, increasing production of lactate eventually outpaces the body’s ability to clear and utilize it, and the level of lactate in the blood and muscles rises dramatically. In cycling, this tipping point correlates with a power output that can be sustained for between 20 minutes and an hour.

The exercise intensity at which this tipping point occurs has been referred to by several different names, including anaerobic threshold, anaerobic lactate threshold, and most accurately Maximal Lactate Steady State (MLSS). Commonly, it is simply called Lactate Threshold (LT), and exactly how to objectively define it is a long-standing subject of debate. A blood lactate concentration of 4.0 mmol/L is often cited, but evidence shows this is a simplistic and arbitrary definition. However it is defined, measuring an athlete’s blood lactate level as their power output rises will eventually reveal a sudden and dramatic increase, and around this time the athlete will experience a decline in performance.

The underlying cause of this performance limitation is complex and controversial. It probably involves the inability to fully utilize the lactate itself, as well as muscular acidosis caused by metabolic production of hydrogen atoms. It is almost certainly not related to the accumulation of lactic acid in the muscles, debunking a long-standing myth.

Whatever the exact cause or causes, the body’s ability to clear lactate from the blood is definitely a factor in the ability to sustain power on a bike. Luckily, lactate clearance is highly trainable.

How to Test Lactate Threshold

Lactate threshold testing can only be accomplished in a lab, by periodically drawing blood during a graded exercise test on a stationary bike. Analyzing blood lactate content as intensity rises reveals the power output at which lactate levels dramatically increase- a rider’s LT.

As with all things lactate-related, there is controversy regarding accuracy and applicability of test results. Some studies show that different testing protocols can yield inconsistent results with the same athlete, and that other factors such as glycogen depletion may adversely affect the data. However, lactate threshold testing is widely available, and along with VO2 max testing is often sought by athletes in search of objective measurements of their abilities.

Lactate Threshold: Trained Vs. Untrained Athletes

Regardless of ability, all athletes experience a similar decline in performance as intensity increases and lactate production outpaces the body’s ability to clear it. However, where the Lactate Threshold falls on an athlete’s power curve can vary dramatically. Research shows untrained athletes may reach LT at 50-60% of their VO2 max, while an Elite athlete may be able to ride closer to 95% of VO2 max before reaching Lactate Threshold. This means well-trained athletes can efficiently sustain a higher relative intensity before reaching their physical limit.

While VO2 max is generally slow-to-improve through training, riders with similar VO2 max measurements often possess very different actual abilities. This disparity can often be explained by differences in lactate threshold. If two athletes have the same VO2max but one has a higher lactate threshold, that athlete will be able to ride harder for longer.

How to Train to Increase Lactate Threshold

Once Lactate Threshold is reached the sustainability of an effort plummets, and the goal of training is to delay the onset of this limiting factor. By increasing the power output at which you can ride before reaching your LT, your ability to generate the same wattage for longer will improve. This effectively allows you to produce more power without working harder in the process.

Lactate is primarily produced by glycolysis and anaerobic high-intensity efforts. Ironically, the ability to clear it from the bloodstream is most effectively developed through lower intensity training, which improves mitochondrial density and aerobic efficiency. This is one reason why developing a strong aerobic base is so important, and Sweet Spot training is the most effective and efficient way to do just this. Additionally, studies show the fitter you get, the more intensity is required to continue improving Lactate Threshold, a good argument in favor of increasing intensity through specialization as your season progresses.

Because the process of testing LT is relatively onerous and requires specialized laboratory equipment, most riders never directly undergo Lactate Threshold testing. However, Functional Threshold Power (FTP) correlates closely enough with LT to serve as a useful proxy. Power at LT is sustainable for 20-60 minutes, and FTP is the theoretical power a rider can sustain for an hour. By using FTP to structure training zones and track improvements, an athlete can effectively target and increase their lactate threshold without directly measuring it.

Training Lactate Threshold with Sweet Spot Training

Sweet Spot training is a time-effective way to increase your Lactate Threshold. Sweet Spot workouts contain intervals that range between 88-94% of your FTP or just below threshold. Riding just below your LT drives aerobic adaptations without overwhelming you with training stress. While training in other power zones can increase your LT, Sweet Spot strikes a balance between productivity and fatigue so that you can complete multiple Sweet Spot workouts in one week.

Sweet Spot workouts strengthen your aerobic energy system, increasing capillaries and oxygen utilization. That means more tiny blood vessels to deliver blood (oxygen & nutrients) to the muscles. These physiological adaptations improve your ability to process and clear the metabolic byproducts from anaerobic glycolysis.

Example Workouts

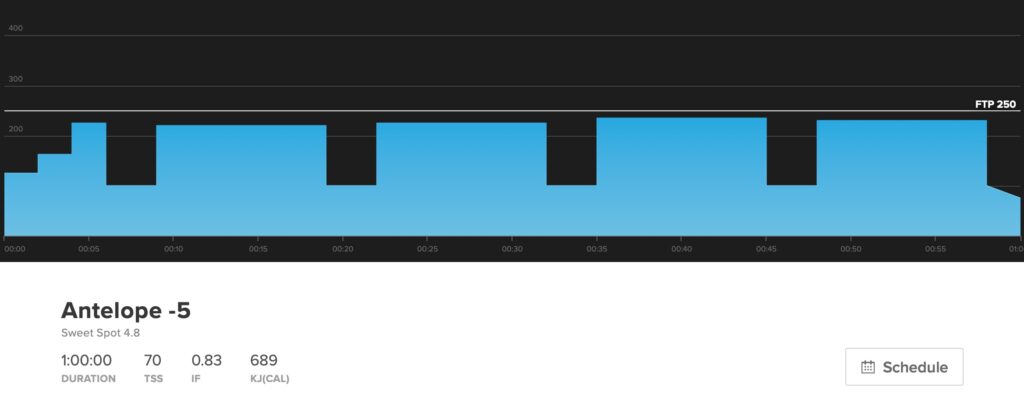

Antelope -5 is a Sweet Spot workout that contains four, ten-minute Sweet Spot intervals with the key aims of furthering aerobic capabilities and increasing muscle endurance. Once you have this workout down, you can shoot for Eichorn, which is twenty-minute intervals. If Antelope -5 is a bit tough, you can try Carson with shorter intervals.

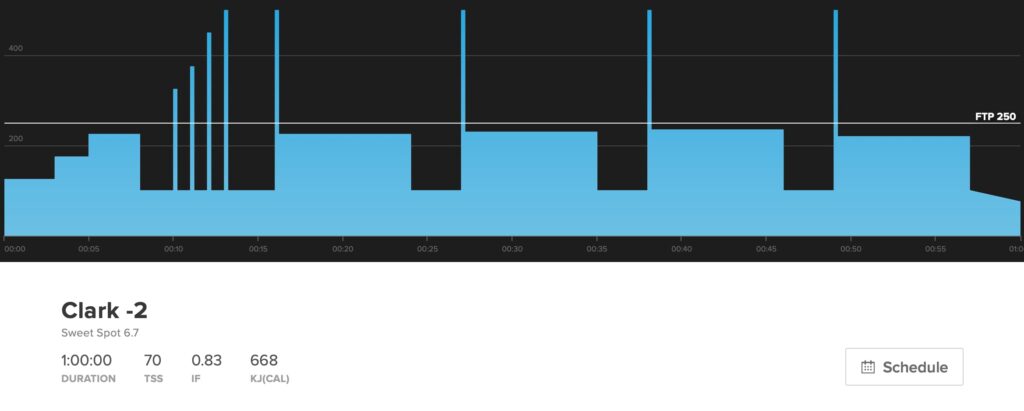

Clark -2 is 4×8-minute efforts between 88-94% FTP directly preceded by a 12-second round of big gear, high-force stomps. The primary goal is to further muscular endurance by improving glycogen storage capacity, lactate tolerance, and the capacity for more intense workouts later on while increasing power output at moderate intensities.

Conclusion

Lactate, Lactate Threshold, and Lactic Acid are among the most commonly misunderstood concepts in sport. Far more than just a byproduct of metabolism, lactate is a crucial fuel source and metabolic component, and is a source of continuing controversy and research. Lactate Threshold is one of the most important determinants of cycling ability, and whether you measure it directly or use a secondary metric such as FTP, improving it can come with great benefits in performance. Finally, Lactic Acid is probably not much of a factor at all, likely not present in the body in any quantity and definitely not the source of that burn in your legs.

For more cycling training knowledge, listen to Ask a Cycling Coach — the only podcast dedicated to making you a faster cyclist. New episodes are released weekly.

References/ Further Reading

- Brooks, George A. Intra- and extra-cellular lactate shuttles. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: April 2000 – Volume 32 – Issue 4 – p 790-799

- Cairns SP. Lactic acid and exercise performance : culprit or friend?. Sports Med. 2006;36(4):279-291. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636040-00001

- Faude, O., Kindermann, W. & Meyer, T. Lactate Threshold Concepts. Sports Med 39, 469–490 (2009). doi:10.2165/00007256-200939060-00003

- Gillium, T.L. & Kravitz, L. (2008). Assessing the lactate threshold. IDEA Fitness Journal, 5(2), 21-23.

- Goodwin ML, Harris JE, Hernández A, Gladden LB. Blood lactate measurements and analysis during exercise: a guide for clinicians. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(4):558-569. doi:10.1177/193229680700100414

- Hall, M.M., Rajasekaran, S., Thomsen, T.W. and Peterson, A.R. (2016), Lactate: Friend or Foe. PM&R, 8: S8-S15. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.10.018

- Kravitz, L. & Dalleck, L. (2005). Lactate threshold training. Network, The Official Magazine of Australian Fitness Network, Autumn, 27-30.

- Lactate Profile. (n.d.). UC Davis Health Sports Medicine. Retrieved July 29, 2020 from https://health.ucdavis.edu/sportsmedicine/resources/lactate_description.html

- Lactate Threshold Testing. (n.d.). University of Virginia Exercise Physiology Core Laboratory. Retrieved July 29, 2020 from https://med.virginia.edu/exercise-physiology-core-laboratory/fitness-assessment-for-community-members/lactate-threshold-testing/#:~:text=The%20lactate%20threshold%20is%20the,period%20of%20time%20without%20fatigue).

- Millán, Iñigo San; González-Haro, Carlos; Sagasti, María. Physiological Differences Between Road Cyclists of Different Categories. A New Approach.: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: May 2009 – Volume 41 – Issue 5 – p 64-65 doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000353467.61975.ae

- Parks, Scott K.; Mueller-Klieser, Wolfgang; Pouysségur, Jacques (2020). Lactate and Acidity in the Cancer Microenvironment. Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 4: 141–158. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033556.

Header photo credit: Alonso Tal